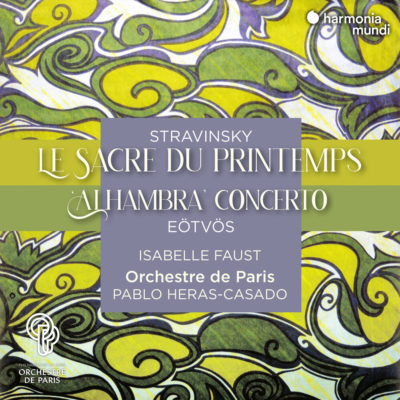

Recording of the Week: Stravinsky & Eötvös from Pablo Heras-Casado and the Orchestre de Paris

09 Apr 2021

Recording of the Week. In the wake of the flurry of new recordings commemorating the 150th anniversary of Berlioz’s death two years ago, it’s a little surprising that Igor Stravinsky’s fiftieth ‘death-day’ (to borrow a phrase from JK Rowling) this week has been marked almost exclusively by reissues – perhaps pandemic restrictions played a role, given the logistical challenges of mounting COVID-safe Petrushkas, Rites of Spring and Firebirds in the studio, let alone the concert-hall. The shining exception, however, is a terrific new Rite from Pablo Heras-Casado and the Orchestre de Paris, recorded in Paris in September 2019 and coupled with an ear-opening world premiere by the Hungarian composer Péter Eötvös.

It’s the Spanish conductor’s first recording with this orchestra, and the rapport he’s built up with the musicians through regular live performances is everywhere in evidence in a work where trust and synergy are especially vital. He’s superbly attuned to the orchestra’s special characteristics (an exceptionally silky string sound, and voluptuous rather than edgy brass among them), and exploits them to maximum effect in an account which plays up the work’s French connections rather than its Russian roots: the Debussy-ish qualities of certain passages in the ‘Danses des adolescentes’, the ‘Rondes printanières’ and the ‘Cercles mystérieux’, for instance, resonate loud and clear. (What a pity that there wasn’t quite enough room here to include La mer, which opened the Paris concert, but one can’t have everything).

Elegance and transparency aren’t adjectives you’d necessarily associate with this score, but Heras-Casado supplies both in spades, and the pay-offs are fascinating, revealing a wealth of inner detail that often gets eclipsed elsewhere. (I don’t think I’ve ever been so aware of what’s going on in the middle of the textures since I attempted to sight-read the viola-part in a performance some fifteen years ago – fortunately an experience which I will never, by definition, have to repeat).

If you’re used to the red-in-tooth-and-claw energy and bottom-heavy sonorities of recordings by the likes of Igor Markevich, Leonard Bernstein and the composer himself, you might need a while to adjust to Heras-Casado’s lighter touch – but I’ll wager he won’t leave you feeling short-changed by the end, the piece’s brutal climax coming as a genuine shock in the wake of the sensuous, almost urbane beauty of what’s gone before. The overall experience is akin to attending a sophisticated, decadent soirée which spirals gradually but inexorably out of control, and the impact is quite something, even if you know the piece inside-out.

The coupling, too, is an astute one, as Eötvös’s Violin Concerto No. 3 ‘Alhambra’ is not without some Stravinsky-esque moments of its own. Commissioned by Heras-Casado (a Granada native) and premiered at the Palacio de Carlos V as part of the Festival Granada in summer 2019, it’s a 23-minute single-movement roller-coaster of a piece which evokes night in the palace in all its unsettling glory, as the soloist (Isabelle Faust, to whom the work was dedicated) is shadowed by the ghostly presence of a scordatura mandolin on her nocturnal wanderings in a sort of Danse Macabre.

The piece begins and ends with a haunting, flamenco-ish solo from Faust, who relishes the Moorish intervals and anxious melancholy of the writing here, but this is no musical postcard in the tradition of Lalo’s Symphonie Espagnole or Falla’s Nights in the Gardens of Spain – Eötvös’s idea of local colour is something far more uncanny and ephemeral, the whispers of Spanish dance-rhythms receding as quickly as they appear, and the musical ciphers representing the names of soloist and conductor introducing an almost Bergian quality in places. Faust, as ever, summons an astonishing range of colours from her instrument and from the music: there are some especially striking passages early on where the bow’s vertical journey (between bridge and fingerboard) is almost as important as its horizontal movement, and the interplay with her mandolin doppelgänger is beautifully done.

A little bird (or, more prosaically, the advance release-schedule) tells me that more Stravinsky anniversary recordings will appear later this year, but I’ll be surprised if many of them surpass Heras-Casado’s Rite – and the Eötvös is far more than a makeweight.